IV. Start Farming

Understanding Licenses, Permits and Certifications for your Farm

Section Author:

- Ben Beale, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension – St Mary’s

As with any business, your farm operation is subject to several laws and regulations. Farm operations also receive several exceptions or special provisions regarding taxes, land operations and the like. Below is a short listing of the commonly required permits or certifications for a farm. There may be others depending on your county, crop or sales channels.

Nutrient Management Plans

Farmers with either gross income of at least $2,500 or 8 more animal units (1 animal unit is 1,000lbs) are required to have and follow a Nutrient Management Plan. These plans can be developed by a nutrient management advisor in your county Extension office or through private industry. You may also become certified to write your own plan. Plans are normally updated annually. More information is available from the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

Nutrient Voucher Applicator Card

Farm operators who apply nutrients (fertilizer, manure, compost) to at least 10 acres of land are required to have a nutrient applicator voucher. The requirement only applies if you, as the operator, apply the nutrient source. If a custom operator or fertilizer company spreads the nutrients, they are required to have a voucher. Vouchers can be obtained by attending a two hour voucher class once every 3 years. The class is conducted by the University of Maryland and there is no test or fee associated with the voucher. More information is available from the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

Private Pesticide Applicator Certification

Farmers who want to purchase and apply Restricted Use Pesticides must first become certified as a private pesticide applicator. No certification is required to purchase general use pesticides, though you must abide by all label instructions. Certification is obtained by passing an examination administered by MDA. The certification is renewed every three years by attending a 2 hour recertification course. University of MD Extension provides review courses, has study materials and hosts the test and recertification in county offices. More information is available from the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

Soil Conservation Plans

Soil Conservation Plans are voluntary plans which provides a blueprint for water and soil conservation practices on the farm. They are developed through the county based Soil Conservation Office. The plan can be a valuable tool for farmers to manage resources and improve profitability. A conservation plan is a working document designed to fit each individual farmer's needs. More information is available from the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

Agriculture Use Assessment

Maryland law provides that lands which are actively devoted to farm or agricultural use shall be assessed according to that use. Assume that a 100 acre parcel of land has a market value of $3,000 per acre. The total value of the parcel would be $300,000 (100 x $3,000). The same 100 acre parcel receiving the agricultural use assessment based on a value of $300 per acre would be $30,000 (100 x $300). The taxes using a combined tax rate of $1.132 per $100 of assessment would be $339 [($30,000 ÷ 100) x $1.132] under the agricultural use assessment and $3,396 [($300,000 ÷ 100) x $1.132] under the market value assessment – a difference of $3,057 or $30.57 per acre (source: MD Department of Assessments and Taxation). More information is available from the Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation.

Organic Certification

Agriculture producers who plan to sell, label, or represent products as “organic” must meet the requirements of the National Organic Program (NOP) and be certified. The certification process typically takes three years, though there are exceptions. More information is available from the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

Building Permits for Farm Structures

The requirements for building permits for farm structures vary by county. Many counties, especially in the rural tiers have reduced permitting requirements for farm buildings. New storm water management regulations are also now required for farm buildings which exceed a certain size. Always check with your local Planning and Zoning office for the county specific requirements.

Marketing and Food Processing

The sale of processed or adulterated food is regulated by several agencies. There are also regulations which affect the sale of products directly from the farm (direct sales) and requirements for collection of sales taxes. For a complete description of regulations surrounding marketing and food processing, visit MREDC's Food Processing module.

Water Appropriation and Use Permit

Required if you plan to withdraw more than 10,000 gallons of water a day based on an annual average withdrawal, from surface or underground waters for agricultural activities. Issued by the Maryland Department of the Environment.

Human Resources Management and the Hiring Process Basics

Section Author:

- Margaret Todd, Law Fellow, Agriculture Law Education Initiative

Disclaimer: The following is intended for educational purposes only and is not legal advice.

Whether hiring a full-time farm manager or seasonal farm hands, the hiring process should be taken seriously. Employers should take the time to comply with labor laws throughout the process of advertising, hiring and employing workers.

Employment Relationships

Maryland is an “at-will” employment state, meaning that in the absence of an express contract, agreement, or policy, an employee may be hired or fired, with or without cause, and without any previous notice, for any non-retaliatory and non-discriminatory reason. However, an employer can either orally or in a written document negate the “at-will” employment presumption by agreeing to only terminate employees for cause, only in accordance with established policies, or by specifying a guaranteed duration of employment. In some cases, however, employment contracts are legally required. For example, the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Workers Protection Act (MSPA) requires farmers to use employment contracts with specific provisions when hiring migrant and seasonal employees, and employment contracts are also necessary when hiring H-2A Visa workers.

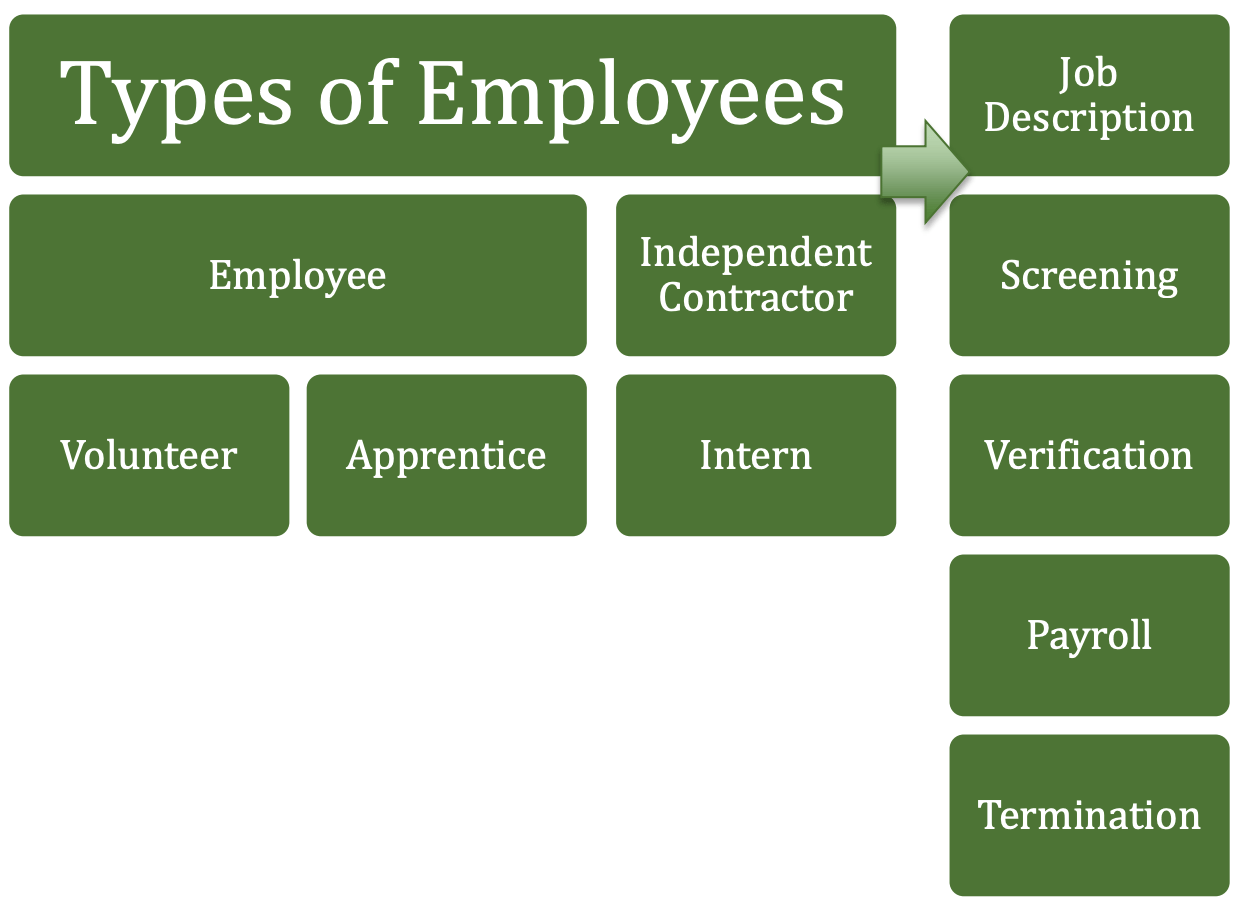

Types of Employees

When an employment relationship is established, the employer will have various legal responsibilities, depending on the type of employee (discussed later in Agricultural Labor Laws). Types of employees include migrant workers, seasonal workers, H-2A visa workers, interns, apprentices, and office workers. Family members are often recruited to help on the farm as well. Immediate family members are not considered employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) or the various Maryland labor laws and are not entitled to minimum wage or overtime.

Employee versus Independent Contractors

Understanding the difference between an employee and an independent contractor is important for an employer. Employers have significantly fewer obligations when engaging independent contractors. An independent contractor has been judicially defined as "one who contracts to perform a certain work for another according to his own means and methods, free from control of his employer in all details connected with the performance of the work except as to its product or result.”

Failing to properly classify a worker as an independent can have steep financial consequences. Even if there is a signed agreement declaring that a worker is an independent contractor, that is not enough by itself to prove that an employer-employee relationship did not exist. Instead, the predominant consideration is the level of behavioral and financial control the employer maintains over the worker.

Interns and Apprentices

Interns and apprentices are a popular hiring option for reducing the farm workload while also helping the next generation gain practical farming knowledge and experience. Internships and apprenticeships are not interchangeable terms. Separate guidelines provided by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) must be used to determine a worker’s legal status as either an intern or an apprentice.

Internships provide work experience that corresponds to the intern’s academic program and accommodates the intern’s academic commitments. Internships are usually short term and the intern receives academic credit in place of monetary compensation. Under the FLSA, interns are not considered “employees” and can therefore be compensated at less than minimum wage. Intern classification is determined by DOL’s “primary beneficiary test,” using seven factors weighed all together to examine the “economic reality” of the employment relations.

Apprenticeships combine paid on-the-job training with classroom instruction to prepare workers for highly-skilled careers. Apprentices learn from an experienced mentor for typically one to three years and may receive increases in pay as their skills and knowledge increase. Although under the FLSA apprentices are considered employees, an apprentice may be paid less than minimum wage. Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation (DLLR) also oversees work-study apprenticeship programs in Maryland.

Volunteers

Volunteers are not paid for work but nonetheless willingly provide their time and effort. Employers using volunteers for their farm operations must remember that individuals cannot waive their right to a minimum wage, and employees may not serve as unpaid or underpaid volunteers in for-profit private sector businesses. A farmer may allow the collection of leftover crops, known as gleaning, with volunteers for a non-profit organization coming onto the farm to glean. Farmers will generally not be liable for injuries to gleaning volunteers of other organizations as long as they provide a warning of known dangerous conditions on the farm.

Job Descriptions

Accurate job descriptions help the farmer attract qualified candidates and help applicants obtain a realistic preview of the job. Job postings should include the job title, a brief narrative summary of duties and responsibilities, hours, wage, and benefits, and required qualifications. If the position requires the ability to do specific tasks, like heavy lifting, operating heavy machinery, or following written instructions, the job advertisement should clearly state those types of essential job functions. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), employers are required to make reasonable accommodations to qualified employees with disabilities, unless doing so would pose an undue hardship to the employer. Including a list of the essential job functions is important; doing so will allow a farmer to terminate a worker for not being able to fulfill known job requirements. Farmers who anticipate hiring migrant or seasonal workers should keep records of written job descriptions, including “the crops and kinds of activities on which the worker may be employed,” for reporting purposes.

Screening and Interviewing Applicants

Once applications are submitted and it is time to screen and interview applicants, employers must keep the job qualifications clearly in mind when coming up with interview questions to figure out who is capable of performing the work. Both state and federal laws prohibit employment discrimination based on personal attributes that have no bearing on the ability to perform the work, i.e. race, religion, national origin, ancestry, mental or physical disability, marital status, age over 40, medical conditions, sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Employers must craft interview questions with care to avoid inadvertently asking questions that will expose details on personal attributes like marital status, health, etc. Establishing a neutral and relevant skills test to every applicant is one way to avoid complaints of unfair treatment.

Employment Eligibility Verification and Form I-9

Employers are required to verify an employee’s identity and eligibility to work in the United States, which is completed by having the employee complete a Form I-9, Employment Eligibility Verification (I-9). Ensuring each new employee fills out an I-9 is the employer’s defense against a potential claim of knowingly employing an unauthorized worker. According to the U.S. Citizens and Immigration Services (USCIS) Employer Handbook (M-274), all employers must complete and have an I-9 on file for each person currently on their payroll. Employers are required to physically examine identifying documents within 3 days of hiring an employee; the Employer Handbook provides guidance on which documents are acceptable. Further, employers must retain I-9s for all terminated employees for three years past the hire date, or the date of termination plus one year. Employers should keep careful records in case of a USCIS audit.

Payroll and Recordkeeping

Federal and state laws regulate how and how often wages should be paid, require recordkeeping obligations for employers, and require the employer to withhold taxes from employee earnings. Employers are required to pay employees no less often than every two weeks, or semi-monthly. Employers must provide a paystub to each employee on each payday, regardless of the basis of pay. Paystubs must include: hourly rate, or piece rate and the number of units earned, for each activity; correct number of hours worked; total earnings for the pay period; amount and purpose of any deductions, such as for taxes, rent or meals; net pay; employer’s name, address, and identification number, and; worker’s name, address, and social security number. Payroll records must be kept for at least three years. Records used for computing wages, such as time sheets or field tally totals, must be kept for at least two years. Farmers who hire migrant, seasonal, or H-2A workers will have additional record keeping obligations.

Termination

Various labor laws place restrictions on employee termination, including anti-retaliation provisions prohibiting employers from firing employees in retaliation for engaging in protected activities, like filing a workman’s compensation claims, filing a lawsuit for injuries sustained on the job, becoming a “whistle-blower,” missing work for jury duty, helping form a union, or refusing to do hazardous work. Employers should be careful and document reasons for employee termination to protect against wrongful termination charges. Upon termination, employers must timely provide all earned income and accrued leave to the terminated employee, or potentially be subject to punitive damages up to three times the amount withheld.

Conclusion

Each step of the way, employers must remember to satisfy various recordkeeping obligations. Consulting an attorney and tax professional is the best way to make sure records are kept in compliance with all federal and state laws in case the farm ever faces an audit. The hiring process can be long and costly, and managing employee performance is an ongoing process. However, the time and effort required to find and retain the best employees is an investment in the productivity of the farm.

Agricultural Labor Laws

Section Author:

- Margaret Todd, Law Fellow, Agriculture Law Education Initiative

Disclaimer: The following is intended for educational purposes only and is not legal advice.

Growing a farm business will usually require finding reliable and skilled workers to help both on and off the fields. Hiring farm workers hopefully means a thriving and productive farm operation, but it should not be done without an understanding of applicable labor laws. Labor laws cover issues like who is identified as an authorized worker, minimum wage and overtime standards, occupational health and safety standards, insurance requirements, child labor limitations, and more.

This chapter will outline the basics of the numerous federal and state laws applicable to farm businesses in Maryland. References to useful and detailed resources are included throughout for further reading on each topic. It is always advisable to seek legal advice when interpreting and applying laws.

Federal and State Labor Laws and Employment Standards

Federal laws establish the national baseline rules for wage and hours, health and safety protections, often require recordkeeping and reporting, and prohibit discrimination in the workplace. States are allowed to adopt stricter laws. Maryland’s employment and labor laws do so by establishing further state level protections for employees.

Federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and Maryland Minimum Wage and Hour Laws

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) is the federal act that establishes the maximum hours for a workweek, the national minimum wage, time-and-a-half overtime standard, and the child labor standards. FLSA applies to all businesses that have at least two employees and at least $500,000 a year in gross sales. Employees working for smaller businesses may still be subject to FLSA protections if they are individually engaged in interstate commerce, in the production of goods for commerce, or in any closely-related process or occupation directly essential to such production. Whether a farmer is running a farm under a business entity or as a sole proprietorship, the FLSA will typically apply to some degree. A business or worker is subject to FLSA if either the enterprise coverage or the individual coverage applies.

Minimum Wage

The Federal government establishes the national minimum wage, but a state may adopt a higher minimum wage for its residents. Maryland’s minimum wage is higher than the federal wage and is expected to increase annually. Localities may also choose to adopt a higher minimum wage, such as Prince George’s and Montgomery counties. Unless an exemption applies, the higher minimum wage, whether it is state or local, is the wage employers must follow and pay their employees.

- Various agricultural workers, however, are exempt from minimum wage requirements. Maryland’s exemptions for agricultural workers largely mirror the federal exemptions. The following are specific types of agricultural employees that are excluded from federal and state minimum wage requirements:

- Agricultural employees who are an immediate family member of their employer,

- Those principally engaged on the range in the production of livestock,

- Hand harvest laborers who commute daily from their permanent residence, are paid on a piece rate basis in traditionally piece-rated occupations, and were engaged in agriculture fewer than 13 weeks during the preceding calendar year,

- Minors, 17 years of age or under, who are hand harvesters commuting daily from their permanent residence, paid on a piece-rate basis in traditionally piece-rated occupations, employed on the same farm as their parent, and paid the same piece rate as those over 17.

Maryland also excludes employees engaged in “canning, freezing, packing, or first processing of perishable or seasonal fresh fruits, vegetables, or horticultural commodities, poultry, or seafood” from the Maryland minimum wage requirements; these employees are still entitled to federal minimum wage payment. Additionally, Maryland allows employers to pay employees under 18 years of age a wage equal to 85% of the state minimum wage, regardless of their type of employment.

Small farm employers also benefit from what is known as the “500 Man-Day Exemption.” Basically, any farm employer that used less than 500 man-days of labor in any quarter of the previous calendar year is not required to pay agricultural workers either state or federal minimum wage. A “man-day” is defined as any day an employee performs “agricultural work” for at least one hour. In order to qualify for the exemption, however, employees must perform agricultural work as that term is defined by law.

Overtime

Under both the FLSA and Maryland law, agricultural workers who are exempt from minimum wage are also exempt from receiving overtime wages. Maryland, however, provides other farmworkers overtime pay after 60 hours/week. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), a common employer mistake is failing to pay overtime to employees whose jobs are related to agriculture but do not meet the FLSA’s definition of agriculture.

To determine whether farm employees are eligible for the agricultural labor exemption, an employer must compare the work performed by the employee to the FLSA’s definition of agriculture, broken down into either primary or secondary agriculture. Employers need to remember that each exemption needs to be examined and applied carefully to avoid underpayment of wages. If an employee in the same workweek performs work that is exempt (fits the definition of agricultural work described above) and work that is non-exempt, the employee is not exempt for the entire week and the minimum wage requirements of the law apply.

Child Labor Standards

The applicable rules for agricultural work hours and duties depend upon the age of the employed minor. Generally speaking, minors can be employed outside of school hours so long as they are not asked to perform hazardous duties and are limited to farm work that is performed on a farm. Minors 16 and younger may not be allowed to work in connection with cleaning or operating power-driven machinery (not including office machines), manufacturing, or in connection with hazardous chemicals. In the agricultural context, working in a yard, pen or stall occupied by a stud animal or a sow with suckling pigs, working inside a silo or manure pit, and handling or applying certain agricultural chemicals are considered hazardous duties that minors are prohibited from performing.

Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA)

Farmers must take steps to ensure their farms are safe and hygienic workplaces and free from recognized hazards that cause or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to the employee. Maryland Occupational Safety and Health (MOSH), a division of the Maryland Department of Labor and Licensing Regulation (DLLR), sets and enforces standards for workplace safety and health. MOSH has adopted the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) rules pertaining to agriculture, although some activities on a small farm are exempt. Regulations include provisions for cool, clean drinking water and well-stocked hand washing and toilet facilities, provided free of charge. Also included are safety measures for tractors and heavy machinery used in agriculture.

Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA)

The Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act (MSPA) is the federal law that governs the employment of migrant and seasonal agricultural workers, creating employment standards related to wages, housing, transportation, disclosure, and recordkeeping. Farmers using farm labor contractors should be aware of the contractor’s practices and use only licensed contractors to avoid joint liability for violations of federal and state laws.

In Maryland, the Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation (DLLR) enforce protections for migrant and seasonal agricultural workers. Failing to fulfill the duties and responsibilities required by the laws can result in substantial civil and criminal penalties for the employer.

Healthy Working Families Act - Maryland Sick Leave Policy

Maryland’s general policy requires employers to provide sick and safe leave to employees who are over 18 years old at the beginning of the year and work more than 12 hours/week. Although Maryland has a sick leave policy, employers are not required to provide sick leave to employees working in the agricultural sector on an agricultural operation. Although farm employers are not legally required to provide paid sick leave, there are many sound reasons to do so, including but not limited to, reducing the likelihood sick workers contaminate produce.

Federal Non-Discrimination Laws and Maryland Equal Pay for Equal Work

As a general rule, discrimination of any kind is prohibited in the workplace. Federal laws prohibiting discrimination include the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), and the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA). Maryland also prohibits sex and gender-based discrimination through the Equal Pay for Equal Work Act. These laws are particularly important to remember during the hiring process when interviewing applicants and when deciding to promote or terminate an employee.

Conclusion

Legally employing people involves careful consideration to ensure employees’ rights are respected. Consult qualified tax, accounting, insurance and legal advisers who are familiar with farming operations to ensure the best planning and employment decisions are made to avoid unnecessary fines or other penalties for failing to comply with federal and state labor laws.

Agricultural Labor Law Links

- Recent Decisions Emphasize the Need for Farmers to Understand Ag Overtime Exemptions

- Child Labor Laws in Agriculture: What You Need to Know

- Is My Farm Exempt? OSHA Confusion Continues

- Sarah Everhart, Is Your Hand-Labor Operation Legal?

- Faiza Hasan, Farmers, Are You Complying with MOSH Standards?

- Cultivating Compliance: An Agricultural Guide to Federal Labor Law

- When is Workers' Compensation Coverage Required for Agricultural Workers?

Farm Insurance Overview

Section Author:

- Margaret Todd, Law Fellow, Agriculture Law Education Initiative

Disclaimer: The following is intended for educational purposes only and is not legal advice.

Whatever the operation may be, risk management is vital to building up an enduring farm enterprise. Successful risk management means understanding your operational insurance needs and the coverage that can help protect your business against loss.

General Liability Coverage

General liability insurance helps protect farm business assets in the face of legal liabilities. When someone is injured on the farm or when someone’s property is damaged due to farm operations, products, or employee actions, general liability insurance helps cover the medical bills and legal expenses – including the payment of a settlement or jury award – that the farmer or farm business would otherwise be obligated to pay out-of-pocket.

Liability insurance policies operate the same as any other insurance policy – the business pays an annual premium and chooses the maximum coverage and deductible amounts. For example, if a farm gets sued for $25,000 for medical costs associated with an injury attributed to a farm hazard, and has $10,000 in legal fees, but the coverage maxes out at $30,000, then the farm is responsible for paying the difference of $5,000.

A farm’s coverage needs will depend on the type of operation and the risks inherent to the business. For example, having customers on the farm creates a higher standard of reasonable care for the business, increasing the potential for liability. Whenever members of the public come onto the farm, liability coverage, above and beyond the standard liability coverage, will likely be needed to protect the business if someone gets injured while on the property. The extent of coverage depends on the specific risks and the frequency of on-farm activities.

Duties performed by employees is another consideration in choosing coverage limits should be the duties performed by employees. An employer’s common law liability risks can include injuries or property damage caused by an employee. If an employee, while performing job related duties, is negligent and causes injuries to third parties, an employer could be held vicariously liable under a doctrine known as respondeat superior. Respondeat superior generally only applies to an employee’s actions carried out while performing duties within the scope of their employment and for the employer’s interests. A general liability policy will typically cover an employer’s vicarious liability to some degree. Meeting with an insurance agent and discussing your operation is the best way to determine the appropriate insurance coverage.

Commercial Property Insurance

Commercial property insurance plans are appropriate for businesses with property and physical assets, such as equipment. Commercial property insurance is important to consider even for farmers living on their farm. General home liability coverage usually will not cover farm business loses. The value of the business property will affect the total cost of the policy and coverage limits.

Likewise, personal assets located on business property are usually not be covered under commercial property plans. Losses from certain types of natural disasters, floods and other major weather events may not be covered by standard commercial property policies; neither are intentional and fraudulent acts by employees or injuries to workers that occur in the workplace.

Farm Insurance

Since farmers often live and work on the same property, many insurance providers offer farm insurance, which is a combination of a standard homeowner’s policy and a commercial insurance policy. Some providers have policies tailored to “hobby” and full-time farms, based on the size and annual income. Each farming operation is unique and a policy can be custom built for the needs of the farmer.

Product Liability Coverage

Product liability insurance is often a part of a comprehensive general liability policy offered by insurance providers and provides protection against financial loss if a farmer is legally liable for injury or damage resulting from the use of a farm product. The provider will need to know all the products sold or planning to be sold – failing to disclose all products may make a policy void in the event of a claim. Product recall insurance is another type of specialized coverage that helps cover the costs associated with removing products from stores and notifying the public of a problem.

Commercial Vehicle Insurance

Maryland requires all vehicles to be insured and sets minimum coverage requirements. Standard general liability polices do not usually cover auto accidents. Commercial auto coverage is needed to cover damages resulting from an accident of a commercial vehicle, including damage to a third party’s property. Cargo coverage is required for the contents or load the vehicle is carrying. Unless specifically listed on the policy, a vehicle policy will not cover animals transported in a truck or trailer. If you routinely transport animals to or from an auction or any other destination, the animals will need to be covered separately on the farm owner’s policy.

Crop Insurance

The Federal crop insurance program started in 1938 and is designed to protect farmers against unavoidable and uncontrollable losses caused by natural disasters. Private insurance companies handle the service delivery side of the program (i.e. writing and reinsuring the policies, etc.). The program is overseen and regulated by the United States Department of Agriculture Risk Management Agency (RMA). RMA sets the rates that can be charged and determines which crops can be insured in different parts of the country. RMA provides policies for more than 100 crops; policy information often varies by crop, from state to state and sometimes from county to county. Federal insurance is also available for dairy and livestock producers. Pasture, Rangeland, and Forage coverage (PRF) is another related protection for livestock producers.

Federal policies are only available through RMA Approved Insurance Providers (AIPs). The private companies are obligated to sell insurance to every eligible farmer who requests it and must retain a portion of the risk on every policy. RMA and insurance industry activities, however, follow a timetable known as the insurance cycle and there are state-by-state enrollment deadlines for farmers to purchase, review, or modify their crop insurance policies. For crops not eligible for coverage under a crop insurance policy, USDA’s Farm Service Agency offers the Noninsured Assistance Program (NAP). NAP provides assistance to producers of noninsurable crops when low yields, loss of inventory, or prevented planting occur due to uncontrollable natural disasters or unfavorable weather conditions during the coverage period, before or during harvest. Producers should contact a crop insurance agent for questions regarding insurability of a crop in their county. For further information on whether a crop is eligible for NAP coverage, producers should contact the FSA county office where their farm records are maintained.

Workers' Compensation Insurance

If a farmer has at least three full-time employees or an annual payroll of at least $15,000 for full-time employees, then the farmer is subject to Maryland’s Workers’ Compensation Insurance law. In addition to wages, the cost of lodging, meals and other benefits provided to employees are included in the annual compensations calculations. In case of accidental personal injury, workers’ compensation insurance funds are used to pay eligible injured employees’ medical and funeral expenses. Employees who accept worker’s compensation benefits for on-the-job injuries waive any right to sue their employers for the resulting medical and/or funeral expenses.

Maryland Unemployment Insurance Program

Maryland law requires agricultural employers who pay wages of at least $20,000 during any calendar quarter of the current or preceding year to employees for agricultural work, or employ at least 10 individuals in a period of 20 weeks in the current or preceding calendar year, to participate in the Maryland Unemployment Insurance program. The Maryland Unemployment Insurance program provides pay benefits to workers who are unemployed and seeking work. The program requires the employer to pay contributions into the Unemployment Insurance Fund on the taxable wages paid to its covered employees. Employees must be advised about their rights to benefits and how to make claims for benefits by a posting in a readily accessible location.

Filing a Claim

Always read the policy documents and ask questions of the insurance agent to gain a clear understanding of the policy’s coverage and procedures. Insurance policies contain statements of what is covered and what is not covered by the policy. Most insurance policies set specific procedures and time limits for filing a claim and require cooperation with the insurance company’s investigators. Policies will differ by provider but many policies require immediate written notice of a possible claim to the producer or insurer. Take and save pictures of the damaged, destroyed, or stolen property, and document any temporary repairs and receipts for repair-related expenses. Do not dispose of any damaged property until the insurer approves the claim.

Conclusion

Insurance is a major expense and investment in the longevity of a farm. Assess the risks inherent to the farm business before shopping around for insurance and comparing prices. As a farming operation grows and changes, so will the business insurance needs. An annual insurance self-audit is a good practice to ensure that new features, employees, pieces of equipment, buildings etc. are covered by insurance policies.

Insurance Overview Links

- Managing Legal Risks for Agritourism Operations

- Specific commodity's coverage in Maryland, see USDA RMA

- For more information on available livestock policies, see USDA RMA, Livestock

- For more information on PRF coverage

- For a list of AIPs, see USDA RMA, Crop Insurance Provider List for 2019

- Locate an insurance agent or approved insurance provider

- For more information on applying for NAP coverage, see USDA FSA Disaster Assistance Fact Sheet

- Employers' Quick Reference Guide, Maryland DLLR

Web Links and Resources - Start Farming

- Maryland Department of Agriculture Licenses and Permits

- Maryland Department of Commerce

- University of Maryland Agriculture Law and Education Initiative Publications Library

Human Resource Links

- When Hiring Migrant, Seasonal, and H-2A Visa Workers

- Four Labor Law Mistakes to Avoid This Season

- Independent Contractor Test

- Employing interns and apprentices on the farm

- Internship Programs FLSA

- Apprenticeship and Training Regulations - Maryland Apprenticeship and Training Program

- Apprenticeship

- Gleaning, Food Banks and a Farmer's Liability

- U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Agricultural Workers

- Staffing the Farm Business, in Ag Help Wanted: Guidelines for Managing Agricultural Labor

- Reasonable Accommodation and Undue Hardship Under the Americans with Disabilities Act

- How Best to Comply with the Relevant Federal and Maryland State Standards

- Agricultural Employer's Tax Guide

- Are You Following the Law When you Fire Problem Employees

Start Farming Review - Questions to Ask Yourself

- Do you know what farm licenses or permits your business will need to operate and sell?

- Does your business plan include employees in the future?

- If you plan to hire employees do you understand your responsibilities as an employer?

- Have your reviewed your insurance needs to protect your farm and personal assets?

- Are you ready to start farming?

MD Beginning Farmer Guidebook home

Next: Conclusion

Previous: Business Planning